Designing the Place That Remains

More in this issueWe're highlighting the way this territory is being transformed. Within this span of time, we've seen the tremendous evolution of territories.

It started out capriciously. Last year, Hala Younes and her friends were chatting about how it would be nice to one day participate in La Biennale di Venezia, a world-renowned exhibition in Venice, Italy that highlights the arts and culture of countries around the world.

Younes, an assistant professor at LAU’s School of Architecture and Design (SArD), wanted to build upon the previous Biennale, in which students from LAU participated in Lebanese artist Zad Moultaka’s exhibit. Younes got the idea to propose the official participation of all of Lebanon in this year’s event.

Now she — along with 10 other faculty and students from LAU and other Lebanese universities — is curating the exhibition Lebanese Pavilion 2018. This is the first time a Lebanese project at the Biennale has been officially endorsed by the Lebanese Ministry of Culture and backed by the Order of Engineers and Architects.

This year’s Biennale theme is The Place That Remains. In advance of the exhibition, in March, SArD hosted a conference on the same topic to prepare for the event. The conference highlighted “the places that remain in Lebanese territory, un-built spaces, their qualities, their histories and their potential,” said SArD Dean Elie Haddad.

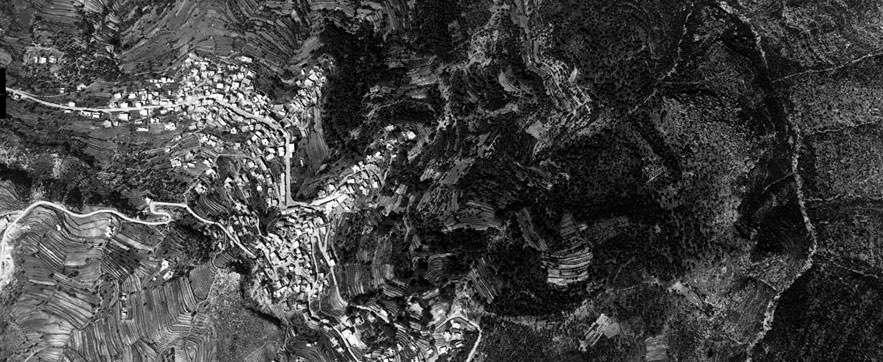

Now on exhibit in Venice, Lebanese Pavilion 2018 includes a 3D model of the Beirut River Valley, featuring a small replica of a 200 square kilometer area. It also includes audiovisual mapping, different aerial maps, and surveys from 1956 and 2015, showing vast differences in land and water use, and urban sprawl and development.

“We’re highlighting the way this territory is being transformed,” Younes said. “Within this span of time, we’ve seen the tremendous evolution of territories.”

In drawing attention to these spaces, and their stunning transformations over 60 years, Younes hopes to show people how to better use land in the future, in terms of architecture, people’s relationship with nature, as well as open spaces and agriculture.

“If we can reuse those public networks and the road network, and if we take care of them, then we’ll have a constellation of open spaces,” said Younes, noting that Lebanon graduates 700 architects every year, all of whom could benefit from a better understanding of their surrounding environments.

Dean Haddad agrees. “This crucial aspect is unfortunately missing in the way architecture is considered as a financial development, without relating it to the wider dimension in which it exists,” he said. “This idea is better developed in other places and contexts, where the symbiotic relationship between the built and the un-built is carefully crafted and maintained.”

Lebanese Minister of Culture Ghattas al-Khoury is hopeful about the exhibition’s impact in Lebanon. “We ought to applaud this project, which is the result of the joint efforts of a number of institutions,” he said at a press conference announcing Lebanese Pavilion 2018. “I hope that this cooperation will serve as an example to all of us — politicians, businessmen and researchers — proving that constructive support always pays off.”

In the end, Haddad said, “We hope that this exhibition will play a role in raising awareness of this important dimension in architecture, in Lebanon specifically and the region at large. This will be an important first step also in the process of future interventions.”