Berytus the Mother of Laws: An Oxymoron?

More in this issueFirst-ever printed book on Beirut speaks volumes about its people and culture.

It might come as a surprise to some that at one time in Lebanon’s rich history its capital was known as the “mother of laws.”

Admittedly, that was millennia ago, as of the reign of Roman Emperor Alexander Severus in the 3rd century through to that of Justinian Augustus in the 6th. But a closer look at why Beirut had earned the prestigious title of Berytus Nutrix Legum reveals traits of its people and culture that survive to this day.

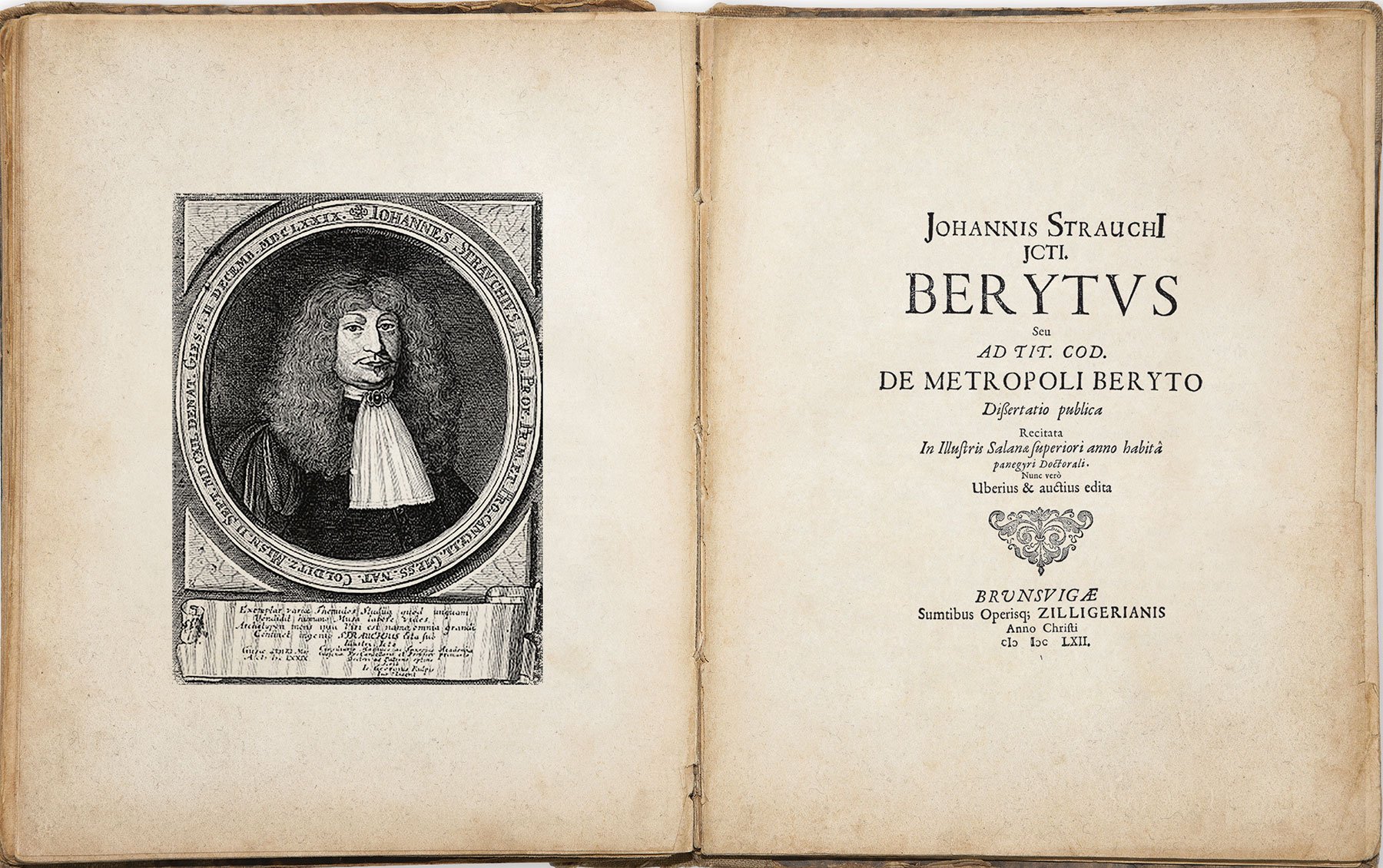

The first-ever printed book on Beirut, recently unearthed and published by the Center for Lebanese Heritage (CLH), sheds light on the city as a commercial center and a Roman colony, focusing on the origins and function of its “very noble School of Law” – one of the oldest Phoenician academies.

Berytus or the Metropolis of Berytus – published in Latin in 1662 by the German jurist Johann Strauch – was initially discovered by Attorney-at-Law Joy Tabet and USEK Professor of Latin Mireille Issa who put out a French translation with Dar An-Nahar in 2009 on the occasion of Beirut’s nomination as the World Book Capital.

Earlier this year, Director of CLH Henri Zoghaib produced an edition in French, English and Arabic, along with a facsimile of the original, as one single volume.

In his dissertation, Strauch draws on the works of authors, poets, travelers and historians to paint a picture of the “glory” of Beirut, and how the capital came to be the only city apart from Rome and Constantinople where the teaching of Roman law was “permitted, by the public authority of the Emperor.” Favored by Emperor Augustus, Berytus in the 1st century had become a colony under the Italic law. Its citizens were exempt from taxes and automatically granted Roman citizenship and the benefits that came with it.

From the records gleaned by Strauch, Berytus emerges as a “noble and ancient city … renowned especially for the charm of its nature and the clever cheerfulness of its inhabitants,” rich in wheat, wine and oil. It also “owed its reputation to the remarkable linen work” produced in countless weaving and dyeing workshops, “to a point that its fabrics and those of neighboring towns were sent out to the whole world.”

When it came to the privilege of housing a law academy, however, the requirements were stringent. Archives of the ancients, says Strauch, show “how much the neighboring bishops they [the Princes of Germania] sent had examined the nature of the place, the temperature of the air, the mores of the inhabitants … and the safety of the place.”

A law academy demanded an environment where learning was revered, and “where the habits of townspeople were not foreign to the spirits and morals of its students,” as there had been previous instances where cities had revolted against the establishment of universities, going as far as attacking the teachers and students “with impunity.”

Phoenicia, on the other hand, was “not only distinguished from the other nations by the glory of having invented letters,” but also by “a clever species of men, remarkable in the works of war and peace, in writing and literature, as well as in other arts.”

Among illustrious Berytians, Strauch cites grammarian Marcus Valerius, Mnaseas of Berytus – who wrote about rhetoric in the Greek dialect – Locrius who published elegies, and prolific grammarian Lupercus, among others. “Who would then doubt,” concludes Strauch, “that the glory of literature and arts was not naturally and almost intimately associated with Berytus?”

The nation’s devotion to “noble studies with ease and diligence” eventually extended during Roman rule to the “science of law, to which it dedicated Berytus’ headquarters and houses.” The students’ insatiable thirst for knowledge and education drove them to request a special dispensation from Rome not to be diverted from the study of law to fulfil their military or public duties until the age of 25. By the 4th century “Berytus began to shine through the study of law, ‘mother of these studies.’”

At the peak of Berytus’ glory, disaster struck. In 551 AD, during the reign of Justinian, an earthquake razed the city to the ground, claiming the lives of the locals and the foreigners who had come to study Roman law. Undeterred, the professors transferred the school to Sidon until Beirut was restored. But no sooner had the city been rebuilt than it was ravaged by a fire, and later besieged by the Saracens, before rising again to become “the largest and most illustrious store and port of Syria.”

There have been many moments of glory in Lebanon’s history, and sadly too many periods of adversity. That Strauch saw it necessary to dedicate an entire chapter, out of five in the book, to the “Diseases, Calamity and the Destruction of the Academy,” is telling.

Yet, throughout, the country has miraculously preserved its sense of hospitality, and the Lebanese their high regard for education, the arts and culture. And if there’s something valuable to be drawn from Strauch’s priceless record, it is this: it was not the law academy that brought fame to Beirut, but rather the noble character of its people.