Is Lebanon Heading Toward Economic Collapse?

More in this issueA critical yet slightly hopeful prospect on shaping Lebanon’s roadmap for economic recovery.

Treading an unsustainable path, Lebanon is struggling to retain the economic resilience that once helped it achieve buoyant growth. The last 30 years of mismanagement of public resources and the adoption of poorly designed public policies have led to a challenging public finances situation that has left the country on the brink of economic collapse.

Undeniably, Lebanon’s economic situation is increasingly alarming. The recent trends of slowing deposit inflows – coupled with constant political quarrels – indicate that Lebanon’s historical economic model may no longer be sustainable.

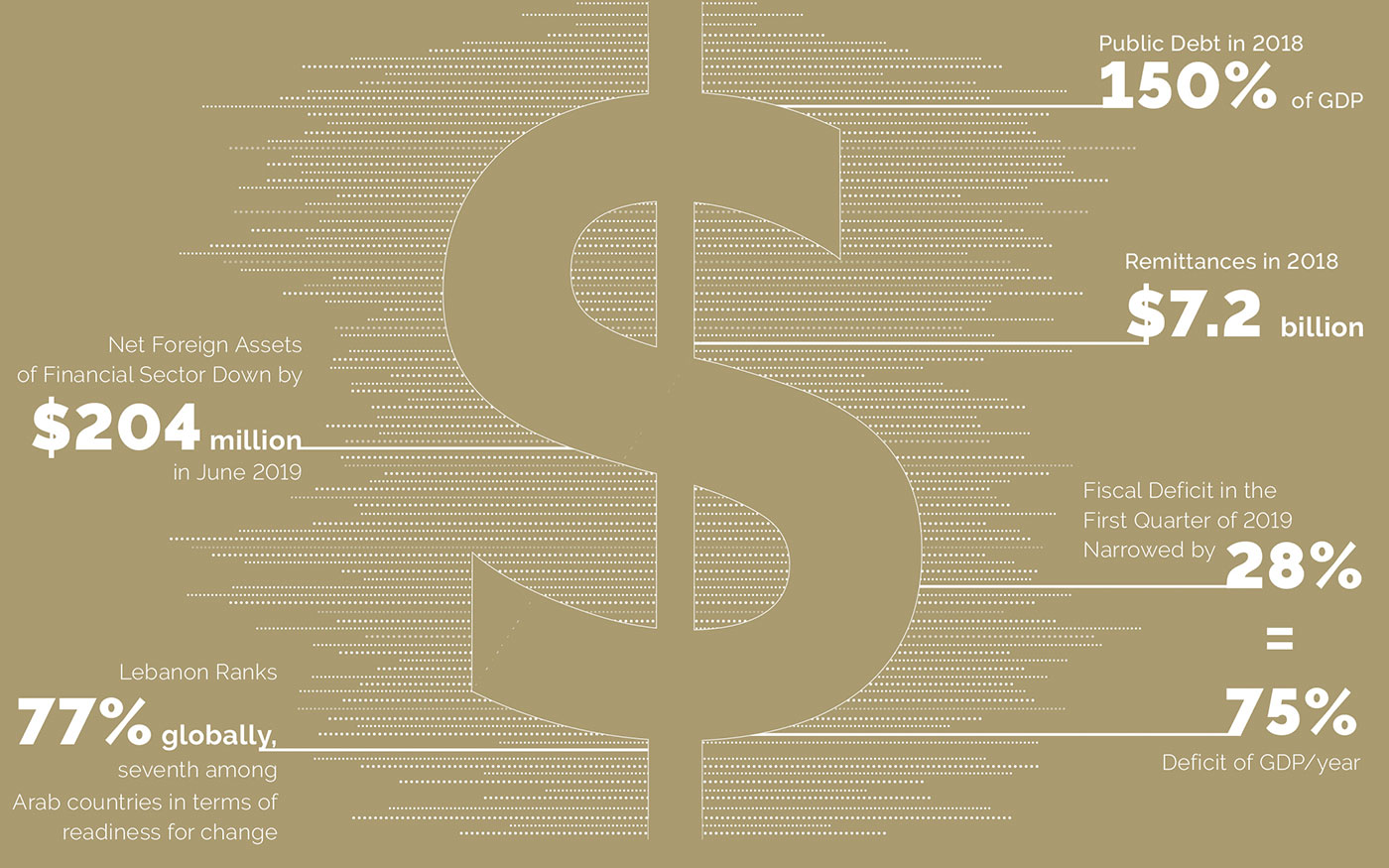

Ranking fifth globally in indebtedness, the country now has one of the biggest debts to Gross Domestic Product (GDP) ratio. Public debt stands today at 150 percent of the country’s GDP while interest rates and financial market volatility have risen.

All this leaves Lebanon in a “multidimensional and structural crisis permeating the economic fabric at all levels,” says Dr. Ghassan Dibeh, LAU professor and chair of the Department of Economics at the Adnan Kassar School of Business (AKSOB).

Although the central bank of Lebanon still has enough foreign currencies reserve to defend the peg for a few more years, holding the currency peg to the US dollar “will become an unattainable proposition if the budget deficit is not reduced significantly and public debt not put under control,” says Dr. Walid Marrouch, assistant dean of Graduate Studies & Research and associate professor of economics at AKSOB.

While the fiscal deficit was expected to reach double digits in 2018 – in a scenario that highly pushed the public debt – the significant narrowing of the deficit in the first quarter of 2019 is a positive development for the Lebanese economy.

According to Byblos Bank’s weekly report Lebanon This Week (Issue 593), global investment bank Morgan Stanley noted in a recent paper that a “significant recovery in deposits would strengthen the banks’ ability to roll over sovereign debt, while successful fiscal consolidation would reduce the government’s funding needs.”

It also noted that fiscal deficit narrowed by 28 percent year-on-year to $1.4 billion, in the first four months of 2019, “which is equivalent to a deficit of nearly 7.5 percent of gross domestic product on an annualized basis.”

The report, overall, takes a positive view on the fiscal, banking and yield curve in the first quarter of 2019.

For Dr. Dibeh, the increased financialization of the economy with ever-increasing fragility due to high public and private debts, high interest rates and balance of payments stop-go dynamics make the current crisis more difficult to tackle and solve.

“Lebanon has likely never experienced the convergence of several economic dislocations including a secular stagnation of the economy, a rise in unemployment and a dominance of low productivity sectors,” he explains.

Although the CEDRE loans – reported to be more than $11 billion in aid – will increase the total debt and its share in foreign currency, the “Vision for Stabilization, Growth and Employment” adopted by the government during the Paris conference promises to reduce public debt.

As reported by the European Commission, the reform program is set to decrease the budget deficit by one percentage point of GDP per year over five years.

Over and above that, a possible drop in remittances could worsen the banks’ ability to continue financing the public debt. Nonetheless, the World Bank Development Indicators show that remittances from Lebanese diaspora are still high and had increased by around 2 percent in 2018 (to reach $7.2 billion) – a component that can “play a vital role in boosting the consumption and secure foreign currency in the economy,” argues Dr. Ali Fakih, associate professor and associate chair of the Department of Economics at AKSOB.

What makes the situation slightly more critical is the fact that around 80 percent of the government’s budget is currently spent on unproductive expenditures consisting of debt servicing and wages. Such a situation “leaves very little room for a proper fiscal policy that boosts growth and reduces unemployment,” states Dr. Marrouch, but “if used properly, investments in essential public infrastructure can boost long-run economic growth prospects.”

On the upside, tourism, which took a substantial shock during the Syrian conflict, weighing heavily on Lebanon’s economic and social fabric, has shown a remarkable recovery this year with the numbers of tourists holding steady and slightly increasing in 2019.

This sector, the three professors maintain, remains a crucial contributor to economic growth and stands robust to the political instability engendered by the Syrian crisis. As reported in a latest study entitled “Tourism-growth nexus under duress: Lebanon during the Syrian crisis,” conducted by Dr. Dibeh, Dr. Fakih and Dr. Marrouch, “policymakers should focus on investing in infrastructure and other tourism-related facilities that are crucial to the future expansion of the industry.”

In this context, Dr. Fakih stresses that the tourism sector is gradually growing from one year to the next, whereas the decent amount of money spent by the Lebanese expats on visits to their home country “helps recompensate the low spending on consumption.”

What about the oil sector? The discovery of oil or gas in the country has left experts wondering about its pros and cons, and whether it will eventually boost job creation in the market.

“These new jobs will contribute to reducing the unemployment rate especially among the educated youth; a mechanism that is expected to create more economic growth in the long-run,” Dr. Fakih projects. He adds that policymakers will protect this sector from corruption to avoid “a sort of social exclusion and the employment of unqualified people.”

Dr. Marrouch disagrees, as the prospects for oil exploration and production are still many years away, he says; “yet, a number of Lebanese politicians are acting as if the oil windfall is a certainty while avoiding much needed structural reforms.”

Promoting Growth

Though the economic growth has long been sluggish, the way out of this predicament is to promote growth by investing in public infrastructure instead of increasing the public sector’s wage bill as was the case most recently in 2017.

“This can happen through investing in ports, airport, roads, railways and the internet,” says Dr. Marrouch.

Other ways to boost development include introducing competition to monopolistic markets, breaking down cartels and oligopolistic markets and reducing barriers to doing business both for Lebanese and foreign investors.

However, these measures can only be effective when reforms materialize, mainly in the public policy. “That is, long-run financial solutions require important reforms in the political system in order to deliver efficient economic outcomes,” Dr. Fakih concludes.

According to Dr. Dibeh, a radical change is what’s needed the most.

“We have to decide whether we want to keep doing what we are doing and have been doing for the past 25 years or whether we want to chart a new course,” he says. “If the latter, we have to take all necessary measures to build a productive economy, a modern secular political system and a fairer society.”

Lebanon’s financial problems are undoubtedly significant, but possible courses of action are available. These will require a political decision and a consensus among policymakers to help avoid the bitter cup and ensure a transition from an era of economic worries to a gradual containment of risks, a prerequisite for real economic recovery at large.